COLD: Communication breakdown between law enforcement failed Joyce Yost

Apr 13, 2021, 10:10 PM

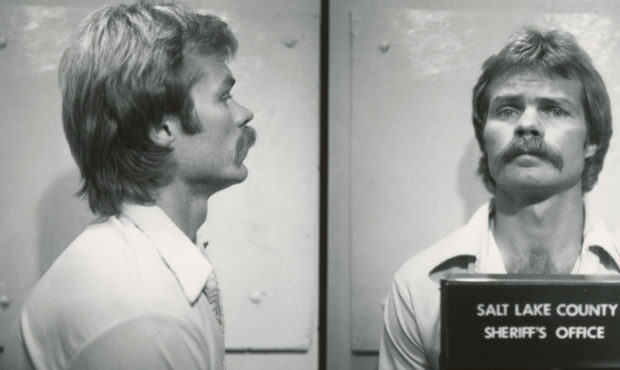

Doug Lovell, seen here in a Salt Lake County mugshot, was arrested several times in the summer of 1985 but released, in spite of facing serious charges related to the rape of Joyce Yost. She vanished 10 days before she would have testified against him. Later, his appeal would focus on trying to withdraw his guilty plea to Joyce Yost's murder. Photo: Police files

SOUTH OGDEN, Utah — A breakdown of communication between law enforcement agencies and Utah’s courts may have failed to prevent the murder of Joyce Yost, who vanished just ten days before she was due to testify against her accused rapist in court.

April 3, 1985

After dinner, drinks and dancing at Pier 3 with a friend, Joyce Yost headed to her South Ogden apartment around 10:15 p.m. She didn’t notice at first, but someone was following her: A little red sports coupe with flip-up headlights bobbed in her rearview mirror.

It soon became clear that whoever he was, he had ill intentions.

“I pulled in my driveway and all the sudden, this little red sports car pulls right in the parking stall next to me,” Yost told police in her initial interview. “He didn’t wait for me to roll the window down or to open the door myself or anything. And he stayed right inside of the car door.”

Yost tried to fight him off, but the stranger raped her. Realizing she had no choice, she “decided at this point to cooperate,” she told officers. He forced her into his car, took her to his own home, and sexually assaulted her again.

Yost turns to the police

After her attacker returned Yost to her apartment, she found her car door open, her things untouched. She debated what to do next. Would her cooperation with her rapist make it tough for police to pursue her assailant?

Her sister, Dorothy, talked her into calling police. So she did, at 1:58 a.m., according to the handwritten South Ogden police dispatch log from that night. Dispatchers sent two officers to her apartment to get initial details and bring Yost in for a medical examination.

Yost’s description of her attack and the evidence in her car helped police corroborate her story. Fewer than 12 hours after Yost parked in her driveway, Clearfield detective Bill Holthaus booked a man named Douglas Lovell into jail on suspicion of rape and sodomy. The next day, Lovell appeared before a judge at Clearfield Circuit Court. The Davis County Attorney’s Office had filed formal charges of aggravated kidnapping, two counts of rape, aggravated sexual assault and forcible sodomy.

Despite the serious charges, his bail was set at $25,000, which he persuaded his father to post on his behalf. Lovell was back on the streets.

Lack of communication fails Joyce Yost

Lovell had repeated run-ins with law enforcement during the months following his initial arrest on suspicion of rape. However, a lack of communication between different jurisdictions at the time prevented officers from learning of the encounters with different agencies. At least two of those instances could have been grounds for having his bail in the rape case revoked.

In May of 1985, shortly a month after the rape, a Utah Highway Patrol trooper cited Lovell for driving under the influence. The stop occurred near Nephi in Juab County.

His wife at the time, Rhonda, would end up bailing him out. But Holthaus, who was working the rape case, was not informed of the DUI arrest.

“At that time, we couldn’t talk to Ogden. We couldn’t talk to any of those other places, except on one frequency,” Holthaus told Cawley.

That frequency, a statewide channel, was used only for emergencies, and this was not considered one.

Lovell was free again. It wouldn’t be the last time.

June 1985

Meanwhile, Yost was preparing to testify against Lovell. She attended a preliminary hearing on June 12, 1985, after which Lovell was due to be arraigned June 20.

But, he never showed up. His lawyer, John Hutchinson, claimed he was healing at home after a back injury.

That same night, police responded to a call at Lovell’s apartment where he reportedly crashed his blue pickup truck while driving intoxicated. Police from Washington Terrace and Riverdale arrested Lovell and began impounding his truck.

Inside the car, they found a handgun underneath the driver’s seat. Possessing the firearm was, at the very least, a violation of the terms of his pre-trial release in the rape case.

The officers were apparently unaware of Lovell’s status as a person out on pre-trial release in a rape and kidnapping case. And, again, no word of this got back to police in Clearfield or South Ogden, where Joyce lived.

What police didn’t realize is that Lovell was on his way in the direction of Yost’s apartment with that loaded handgun. After his arrest, Lovell was again released on bail.

Car theft

With time winding down before the rape trial, Lovell was arrested a third time. Salt Lake City police had obtained a warrant for Lovell after connecting him to a car theft ring.

A Salt Lake City detective booked Lovell into the Salt Lake County Jail on the night of July 8, 1985 on a felony warrant. Jail staff released Lovell a little over an hour later, even though their case could have, once again, been grounds for the Davis County judge to revoke Lovell’s bail.

Joyce Yost had no idea about any of it.

Listen to the full episode

Season 2 of the COLD podcast will take you inside the no-body homicide investigation triggered by Yost’s disappearance. Audio tapes never before made public will allow you to hear Yost, in her own voice, describe the events which preceded her death.

You will learn why police suspected one man, Douglas Lovell, yet were unable to arrest him at the time. And you will see how some individuals and institutions gave — and continue to give — Lovell every opportunity to evade the ultimate penalty.

Hear Joyce Yost’s voice for the first time in the COLD podcast season 2, available to listen free on Amazon Music.

Free resources and help with sexual abuse are available 24/7 at RAINN.org. You can also call 800-856-HOPE (4673).