Faith brought Josh Holt through his darkest hour inside El Helicoide prison

Jul 15, 2020, 12:10 AM

Media reports like this one from Venezuela made their way back to the family of Josh Holt in Utah and raised concerns. Photo from screen grab.

Editorial note: This is the latest in a series of articles related to the KSL Podcast, “Hope In Darkness.” Find all of our episodes and coverage here.

SALT LAKE CITY — A series of serious health problems, the failure of the Venezuelan justice system and dashed hopes combined to sink Josh Holt into a deep depression during the 23 months he spent at El Helicoide prison in Caracas, Venezuela, but his faith ultimately brought him through that depression.

The latest episode of “Hope In Darkness: The Josh Holt Story” digs into how the Utah man became so depressed, he said goodbye to his family — and what it took to lift him out of that dark place.

Health problems exacerbated by poor conditions

Previous episodes of the podcast have highlighted abuses of rights inside Venezuela’s infamous El Helicoide prison. Guards regularly tortured inmates, denied them access to their attorneys and forced them to pay for the right to go to court hearings. Inmates who became sick had to fight for the right to get medical treatment.

From very early on in his prison stay, Holt battled a nagging cough that wouldn’t go away and struggled to breathe at times as his cellmates chain-smoked. Guards refused to take him to see a doctor. His family worried he might have pneumonia or bronchitis; prison officials insisted it was “just asthma.”

Holt began to rapidly lose weight. He struggled to keep food down. His parents worried maybe he had a parasite from the unclean (when available) drinking water.

More than just a little blood

The room Holt shared with three other inmates didn’t have a toilet. At times, to avoid defecating in front of his cellmates, Holt would “hold it” until the opportunity to use a real toilet presented itself. Typically, that came on the occasions when they allowed him to bathe himself in an actual bathroom. This decision to “hold it” combined with a lack of access to drinking water led to constipation.

“And one day, after being constipated for over four to five days, I finally got a hemorrhoid,” Holt said. “I knew how to take care of it, but I didn’t know how to take care of it in this situation.”

In a room with no bathroom nor running water, and no access to ointment or creams to treat the problem, Holt worried about the potential for infection.

“I had no medicine. I had no cream. I had no help,” he said.

Medical help makes it worse

In an exception to their general policy of refusing medical treatment to inmates, the guards agreed to allow Holt to see a medic.

“And when he looked at it, he basically just took his finger and shoved it right back up — and broke it, of course,” Holt remembered. “I started bleeding really, really bad, for the next three to four days.”

It wasn’t just a little blood. Holt soaked through multiple layers of toilet paper several times a day. In light of his other health problems, Laurie Holt, Josh’s mother, scrambled a last-minute news conference on the front lawn of the family’s Riverton, Utah, home. She demanded the Venezuelan government take him to see a doctor, not just a paramedic.

“I am pleading as a mom to the Venezuelan government to please don’t let him lay there and just die,” Laurie Holt said during the news conference.

They never took him to a hospital, but the bleeding did eventually stop. Josh Holt can’t explain why.

“And it was one of those blessings that I just can’t understand. But I was so grateful for it because I was honestly really scared what was going to happen. This isn’t the cleanest environment that I was living in,” he said.

A new gift with a “gift” of its own

Holt struggled with back pain throughout his early months in prison, likely compounded by sleeping on a thin mat on a tile floor.

A short distance away in another cell, his wife, Thamy, also slept on a 2-inch pad on the floor, which she shared with another woman because of crowded conditions.

Prisoners there can pay someone on the outside to get the things of value they need, such as clothes, cellphones and in this case a mattress. Thamy decided that Josh needed the mattress more than she did.

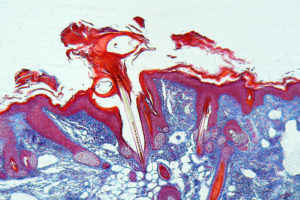

Human skin with a scabies infection, Sarcoptes scabiei, under the microscope and with coloration. Photo: Getty Images

“We did what we could to get a bunk bed,” she told us in Spanish. “We did what was possible to get one, but Josh was having back problems, and I decided that he should sleep in that bed, and I’d keep sleeping on the floor.”

Instead of a bunk bed, the family was able to procure a gently-used mattress, one that came with some “gifts” of its own: scabies.

“I began to itch. And it wasn’t a whole lot at first, but after a week, I started itching a lot and it was everywhere,” Josh Holt said.

Scabies results when microscopic mites take up residence on your skin and burrow into it to lay their eggs. It’s easy to treat on the skin, but you must also address the material where the scabies came from to prevent them from coming back. Anywhere other than a prison, you would fix that with heat: washing in hot water at least 122 degrees Fahrenheit and 20 or 30 minutes in the hot dryer.

The Holts improvised.

“I had to somehow pay someone to give me an iron so I could iron my bed,” he remembered.

“You don’t have any rights”

Josh Holt described this photo, shared to Facebook, as documenting his “worst day” at El Helicoide prison. Photo: Josh Holt

Most inmates did have a few privileges, though. Three times a week, Josh Holt’s cellmates got to go outside for exercise and fresh air. As months passed, Holt continued to watch his fellow inmates exercise that privilege while he remained indoors.

“At this point, I hadn’t seen the sun yet,” he said. “And I really wanted to go outside. …I was like, ‘You know, I’m sick of all this medical stuff. I just need to get sun.'”

One morning, he resolved to go outside with his cellmates. A guard came to the door and opened it to lead Holt’s cellmates outside.

“As soon as I got to the door, the police officer slammed the door in my face and locked it and he said, ‘You’re not going anywhere,'” Holt said. “I said, ‘Please, I want to go out with everyone else. I want to go out to the sun.’ And he said, ‘No. You can’t go.’ And I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because I said no.'”

Holt had had enough.

“And I said, ‘But those are my rights. I’m allowed to go out there,'” Holt said. “And he said, ‘Here in Venezuela, you don’t have any rights.'”

Holt became agitated. He screamed obscenities at the guard. Eventually, another guard came to try to placate him. He told him he couldn’t go out this time, but they’d do their best the next time.

“Well, the next time, they didn’t let me go out. And they didn’t let me go out for a long time. In those two years, when I was held captive there in El Helicoide, I could count on one hand how many times I was able to see the sun. And some of those times were only because they were taking me from the prison to the courthouse. And so I was able to see it for those five to ten seconds, walking from the door to the van where they’d put me,” Holt said.

Better conditions but worsening depression

After passing a year inside El Helicoide, prison officials transferred Josh Holt to a new cell — one in the block of the prison reserved for “political prisoners,” those imprisoned because they disagreed with the Venezuelan government.

When Josh Holt moved to his new cell, he found it had both a toilet and running water. The inmates would disconnect the hose from the toilet tank to fill buckets of water they could use to drink and bathe. Often, the water was full of a brown sediment. Photo: Josh Holt

Josh Holt’s new cell had two sets of triple bunk beds, but it also had a lot more room for the men who locked in there. The new room even had a toilet, which seemed like a luxury after so many months of using newspaper “boats” to go to the bathroom. Feeling grateful, he did something he hadn’t done in months.

“I got on my knees, and I gave a prayer of thanks,” he said.

However, the gratitude only carried him so far. In spite of the improved living conditions, Josh Holt’s depression was deepening.

Hopes dashed again

In July, reporters visited his parents to mark his one-year anniversary in prison. In August, the Holts finally got the pre-trial they had had delayed so many times. It went well — so well, they thought, for sure the judge would decide there wasn’t enough evidence to keep going. They would have to get their freedom soon, they believed.

“And the awesome thing about this moment was, my sister was about to get married,” Josh Holt said.

The team felt so confident in the Holts’ near-future release, they arranged to have a tailor standing by at the couple’s next court hearing to measure Josh for a tux.

Laurie Holt holds a photograph of her son Josh Holt while daughters Jenna, left, Katie and husband Jason look on at her home on July 13, 2016, in Riverton, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

“Well, of course it doesn’t go how they thought it was going to go, and we weren’t freed, and so I wasn’t able to actually be there for my sister’s wedding,” he said.

Family members say Holt’s absence was ever-present at the wedding of his sister Jenna.

“It was bittersweet, I’ll put it that way,” said Jason Holt, Josh’s dad. “There’s a picture of Jenna and I that I saw — I don’t know if it was her Facebook or mine or what. We’re doing the first ‘daddy-daughter dance with her and wiping a tear. I still remember that. It was two-fold. I was so happy for her, but then it was sadness because our family wasn’t all together.”

“I didn’t want to live anymore”

Combined with multiple court dates where nothing happened, Josh Holt hit what he described as his emotional low point in prison.

“I don’t know what it was that finally pushed me over the edge, but I finally had that thought come into my mind, that I was ready just to kill myself,” he said.

Laurie and Jason Holt worried about their son, like any parents would. So did his siblings.

“I remember there was one time that… he called and he was very suicidal,” remembered Derek Holt, Josh’s older brother.

Josh Holt remembers his brother helping talk him out of taking his own life.

“I told them that I loved them all very much, but that this would probably be the last time that I would ever talk to them again. That I was just done. I didn’t want to live anymore, I didn’t want to be in that situation anymore,” Josh Holt said. “And I remember my brother, Derek, grabbed that phone, and he said, ‘Joshua, you stop it right now. I told you that some day I’m going to meet you at the airport. And that’s going to be you walking down that escalator, not as you coming off that airplane in a box.'”

Josh Holt’s parents told him to think about the people he would hurt by taking his life. They asked how he could even consider doing something like that to his wife, Thamy.

“I remember just crying and just telling them, ‘I don’t know! But I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t.’ And my mom would always say, ‘I know, honey. I know. But you have to,'” he said.

Josh Holt turns to his faith

Without access to counseling or medication, Josh Holt had no choice but to try to emerge from depression on his own. As with so many other times, his mother-in-law provided a hand up at a time when he needed it the most. She brought him a copy of Ensign Magazine from his church. Inside was an article about finding joy in chains, the way the Apostle Paul did when he was in prison in Rome.

Holt thought about those words again and again as he mentally clawed his way back into the light from the dark.

“Out of nowhere, I would feel this amazing amount of love and care. I didn’t know how many people there were praying for me, how many people that knew about our story and how many people were really worried about us and just wanted the best for us. And I believe that through the power of those prayers and the power of that support, that often I would just feel this warmth just come over me,” he said. “Sometimes, that would come when I couldn’t handle it anymore, when I was just laying in bed, just crying, soaking my own pillow with my tears. And this warm feeling would come over me, and I’d know that everything was going to be okay, that this wasn’t going to last forever.”

Hope In Darkness releases new episodes weekly on Wednesdays. Subscribe free on Apple Podcasts, Google Play or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Suicide prevention resources

Advocates urge anyone who is struggling or anyone with a loved one who may be at risk of suicide to use the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at any time, by calling 1-800-273-Talk.

Read more of KSL NewsRadio’s coverage of “Healing Utah’s Teenagers” here.

KSL’s combined coverage “Reasons to Hope” is found here.

And resources for help around Utah are here.